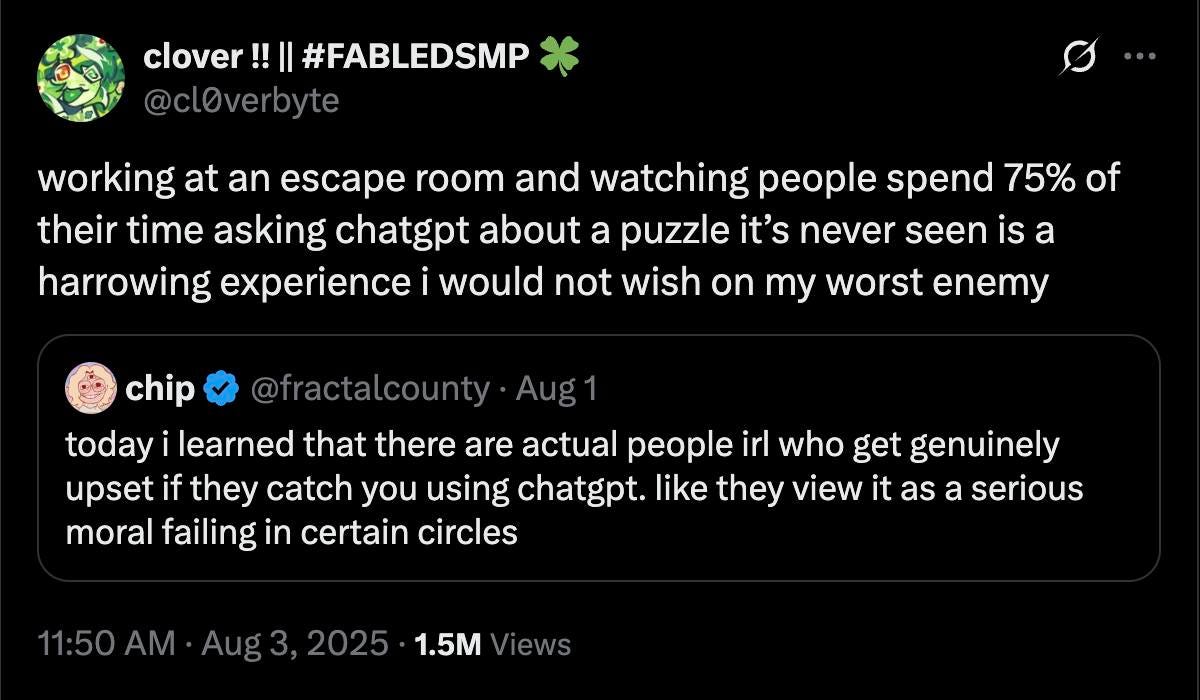

Last week, when I was drafting my Substack post, I saw a little pop-up appear by my cursor.

“Help me write,” it said.

To which I responded: “What the hell?”

Immediately, my mind jumped to conclusions. How dare Substack introduce yet another feature that takes away from the integrity of the platform. First Notes. Then video shorts. Now this. I thought this was a space for writers. Why on earth would we want AI to help us do the very thing we came here to do? Is nothing sacred? Must we incessantly use robots instead of our brains?

Then, after further investigation (and a few rage texts to my friends), I discovered that this was not in fact a Substack feature, but a Google one. Because I was drafting my post within my Chrome browser, Google could tell what I was doing, much like it does in Gmail when it offers to help me write an email response. Email, though, is one thing. I rarely use the feature and I suppose I’m fine with its existence. What do I care if it makes Corporate Chad1sound like he’s halfway literate? I get why it could come in handy. Butting in on my other tabs, however, is another thing entirely.

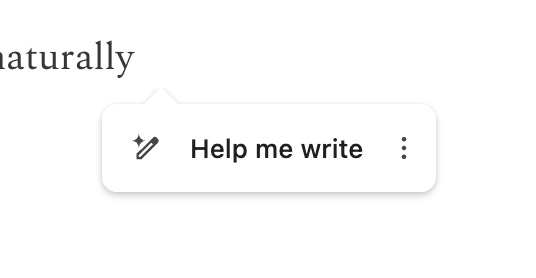

In reading more about the feature, I learned that the “text and content of the page you’re writing on will be sent to Google, reviewed by humans, and used to improve this feature.” I scoffed. Reviewed by humans? How quaint. There of course was also a disclaimer: “Avoid entering personal information (like medical or financial details) or using this tool on sites that contain private or sensitive information.” I scoffed again. There are many aspects of this I find problematic. The first being the fact that this feature warrants a disclaimer in the first place. It’s reminiscent of drug commercials where a narrator spouts a litany of negative side effects at hyper-speed, hoping you’ll be too distracted by the happy people mowing their lawn or taking a salsa class symptom-free to listen. It makes me wonder: If there are negative side effects, perhaps the thing you’re offering isn’t a true solve. Maybe — and this is just a thought — it’s actually causing more of an issue, which in turn only leads me to wonder why it needs to exist in the first place. Sure, I’ll avoid entering any personal details if I ever use the feature, but will that really stop Google from watching me? That’s another thing I have an issue with. As it is, it knew I was on Substack writing a post. I assume it also knows when I’m on my banking website checking my credit card balance.

The age of AI

In the age of the internet, I know few things are truly private. It’s unsettling, but it’s the reality, and things are only getting more complex with AI in the mix. Just the other day I saw a video about how your ChatGPT queries can show up in a search engine result if you don’t change your settings. Apparently, it was part of a “short-lived experiment” with the intention of helping people “discover useful conversations,” but in learning how easy it was for users to “accidentally share things they didn’t intend to,” the company removed the feature last week, according to Fortune. I saw another video a few weeks ago from a woman whose conversation with ChatGPT about her grocery list was conflated with that of two Google VPs trying to prepare for a presentation. It goes without saying how that is particularly problematic.

AI as a tool…and a hinderance

It’s true, AI can be helpful. Like the woman from the video, using something like ChatGPT to build your grocery list can reduce some of the mental load by helping you think of new recipes and identifying the ingredients. It can also help in planning out a schedule. I, for example, recently had it help me create a template to help me optimize my day, which is helpful for someone like me who works from home and tends to lose track of time without structure. I’ve even had it read my astrological chart to tell me things like my soul contract, which honestly made me feel very empowered.2

But for all the ways it’s helpful, it seems AI is more of an impediment in the ways that matter — like critical thinking. Last year, Turnitin, a plagiarism-checking software company, released an AI writing detection tool that has reviewed 22 million essays from college and high school students as of April 2024. It found that “11 percent may contain AI-written language in 20 percent of its content, with 3 percent of the total papers reviewed getting flagged for having 80 percent or more AI writing,” according to Wired. This means millions of essays have likely been written by AI and not by students. As an English major, I know how painful paper writing can be. It’s especially excruciating if you wait until the night before it’s due. I can see how AI would be tempting. However, it’ll never get easier if you never actually do it. Students will never build the muscle if they never use the skill.

It’s a fair concern, and it turns out, research is revealing that AI is actually eroding our critical thinking skills. A recent study from MIT had participants write a series of SAT essays, some of which did so using ChatGPT, others using Google, and others using memory alone. The results, as reported by TIME, are alarming:

Researchers used an EEG to record the writers’ brain activity across 32 regions, and found that of the three groups, ChatGPT users had the lowest brain engagement and “consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.” Over the course of several months, ChatGPT users got lazier with each subsequent essay, often resorting to copy-and-paste by the end of the study.

Essays aren’t the only arena prone to laziness from a reliance on AI. There’s wind on the internet about people using ChatGPT in escape rooms to help them get out, which, you know, defeats the whole purpose of the escape room. It doesn’t seem to matter what the activity is, we appear to be training our brains to rely on AI instead of ourselves. If that’s not sad enough, studies have also shown a correlation between ChatGPT use and loneliness. We’re turning more to technology than we are to each other. It makes us miserable, but we continue to do it. Why? Because on the surface it seems easier. Plus, it’s accessible and it tends to sound pretty darn human.

AI, art, and ethics

As a writer by profession, people often ask me if I’m worried AI will “take my job.” My first instinct is to say no, given the current quality of AI writing (which is abysmal in my opinion). It’s one of the reasons I was so annoyed at Google for trying to insert itself into my drafting process last week. Sure, a part of me recognizes it will likely advance, but the other part knows one thing will always be true: AI is essentially plagiarism. AI technology like ChatGPT is a large language model (LLM), which learns from existing information to mimic human language. When asked a question, it scrapes the internet to piece together an answer, sometimes even “hallucinating” by making things up and quoting nonexistent sources just to satisfy the query. Though we might feel as if the information is new, it might feel like mere brainstorming, since it’s being presented to us in a new way (i.e. in a conversational tone vs. in a search engine results list), it’s just an amalgamation of what already exists on the internet.

I think about this every time I write a Substack post. Theoretically, LLMs like ChatGPT could be using elements of my writing in its answers since none of my content is gated. I don’t love the idea, but it’s the price I pay for publishing openly, I suppose. But what about books or other things behind paywalls and copyrights? What right does AI have to freely scrape that material when everyone else has to pay for it?

It turns out, it doesn’t have one, yet it does so anyway. Or, at least it used to. According to The Authors Guild, as of May 2025, there are approximately a dozen lawsuits “brought in California and New York courts against various AI companies for copyright infringement based on the companies’ unauthorized copying of authors’ works to train their generative AI models,” all of which are class action lawsuits. There are big names involved in these as well. We’re talking George R.R. Martin, Jodi Picoult, and

. These aren’t just household names, these are masters of their craft. Their copyrighted work is likely how LLMs became halfway decent in the first place and reinforces the superiority of actual human thought and creation over AI. The Authors Guild CEO Mary Rasenberger said it well:“The various GPT models and other current generative AI machines can only generate material that is derivative of what came before it. They copy sentence structure, voice, storytelling, and context from books and other ingested texts. The outputs are mere remixes without the addition of any human voice. Regurgitated culture is no replacement for human art.”

She’s right, regurgitated culture is no replacement for human art. Though the act of creation itself is still relatively safe as far as human ability is concerned, it feels risky to share said creations when they’re liable to become further fodder for another LLM. So, where do we go from here? How should these models be sourcing their information, if they even should at all? It’s hard to say. There are few ethics in place. Tech companies will argue that regulations will hinder discovery and advancement, and I can understand that to a degree. It’s why governments and large corporations do everything at a snail’s pace, they’re both burdened by bureaucracy. However, aren’t guardrails necessary since they ultimately prevent us from falling off a cliff? What good is speeding if it just gets us to the point of no return faster?

Theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking predicted this predicament back in 2016. His quote is aptly included in one of the class action complaints:

“Success in creating AI could be the biggest event in the history of our civilization. But it could also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks.”

That was 2016, and this is 2025. The future is here and the risks are real. It feels dangerous to be an artist, especially in such unregulated territory. It’s hard to know if creating means we’re just feeding the machines. It’s even harder to know how hungry they’ll get.

One thing I do know is that I do not need or want AI to help me write. Writing is one of the only things that brings me back to myself, that makes me feel most human. And if that means I have to start drafting my Substack posts on physical paper in order to prevent Google from spying on me, then so be it.

You might notice CEOverthinker looks different. I’ve decided to do a little rebranding! Hopefully you still recognize it in your inbox — and that the makeover makes it all the more enjoyable to read. Regardless, thank you for being here. 🤍

Credit to

for her mention of Chad in her recent post. She painted such a perfect visual with so few words, I had to emulate.If you want to feel like a total badass, I highly recommend it. Just be sure to use the pre-built Astrology Birth Chart GPT, which is already trained to read charts and therefore more likely to give you a better result.

Definitely not a fan of AI for all the reasons you said and it’s frustrating the lack of guardrails we have in place not just for AI but the internet in general. I for one long for a simpler time when one’s words were their bond and privacy mattered.

Oof. This piece makes me want to crawl into a closet and hide (meaning you did such a great job of painting the bleak picture that is the downside of AI 🫠). Haha seriously though—thanks for writing about this! I’ve truthfully avoided AI, probably out of denial, but it’s gotten to the point where I can no longer avoid it.

Good to know that published writing is being used to train models, I didn’t really think about that but it makes total sense. Nevertheless, that won’t keep me from writing either. I agree that this art form is so life-giving! Humans have created art for centuries, even in war, and I don’t think AI can ever take that away from us 💭🧑🎨